We had a seminar the other day on optogenetics given by one of the junior faculty in the neuro side of our department. Those of us in the biomechanics side of things are increasingly interested in the sensorimotor processing necessary to regulate the complex musculoskeletal behaviors we observe. Like good physiologists, we want to be able to disrupt the systems to see how they respond. And the prospect of being able to alter sensory and motor signals reversibly and quickly is particularly intriguing. So we had a chat about it.

Talking with the neuro people is a stark reminder of disciplinary boundaries. Our basic questions overlap on the matter of animal behavior, yet diverge in where we focus our explanatory efforts. To caricature, we examine behavior and musculoskeletal systems, and treat the brain as a black box, and the neuroscientists examine behavior and the brain, and treat the musculoskeletal system as a black box. So things we take for granted, they often are unclear on, and vice versa.

As we were discussing the background of optogenetics, the names of Chlamydomonas and Volvox, the green algae from whose genome the photosensitive ion channel genes have been extracted, came up. Because of my dillettantish path through biology, I have fair amount of botany, and a lot of taxonomy, in my knapsack. And that same wandering path included a pretty extensive flirtation with both cellular physiology, and neuroscience as an undergrad. As we discussed the various components of optogenetics, the light gated ion channels, the promoter sequences, the virus delivery vector, different questions popped into my head. Why did the algae have light gated voltage channels (I'm assuming some sort of phototactic behavior)? Where transposon sequences used to insert the genes into the neurone genomes, so that they would be replicated along with chromosomes, or were they left as free floating strands of DNA? Of course, in our group of mammalian biomechanists and neuroscientists, no one really knew the answers to those questions. And to be honest, they probably couldn't have pulled Volvox out of a eukaryote line up.

I often quip that huge amounts of knowledge about Mus musculus is held by people who don't give a damn about mice. Likewise, many of the people who know about Xenopus development probably know very little about frogs. Model organisms, translational focus and systems based thinking lead to extensive study of organisms that is oddly divorced from an understanding of the organism qua organism. Evolutionary biologists do this too. Systematists famously know little about the biological uses of the various structures they use to construct cladograms. In fact there was a time when such knowledge was considered harmful to establishing relationships, and systematists proudly touted their lack of knowledge about organism function. And molecular biologists have often been not much better regarding the organisms whose genomes they code.

And yet, here, with optogenetics, we have a technology that is born of in depth knowledge of the physiology of single celled algae, the reproductive chemistry of viruses, and the control of genetic expression at the cellular level in mammalian neurons. None of these things are trivial. All of them are products of long research programs within subfields of biology. (The discovery and understanding of transcription factors alone was a huge revolution in cellular genetics, and the histroy of our understanding of viruses and single celled algae is equally fascinating).

It is true that discplines are necessary to provide depth of understanding. It is also true, as Michael Hendricks recently pointed out, that interdisciplinary research assumes the existence of robust, vibrant, INTERESTING disciplines. But for this interdisciplinaryness to occur, there must be people with enough curiosity about what is going on in the neighboring silo to, well, see a possibility for coupling viral vector technologies with voltage gated channels from algae. And when the results of interdisciplinary research become ubiquitous within a field, there are potential risks in remaining ignorant about those aspects of your technique that come from a different scientific history and background.

Without a minimum of curiosity about what's going on in the silo next door, interdisciplinary breakthroughs are impossible. And without a minimum of curiosity about interdisciplinary breakthroughs, our understanding of things we do in our own fields is more black box that we might like.

Sunday, 20 December 2015

The walls are in our heads

Sunday, 15 November 2015

Techne

I was in New York yesterday evening to see Sylvie Guillem's farewell performance. Guillem is one of the great dancer of the past thirty years. Her career has been remarkable both for its brilliance, and for the determination she has shown in charting her own path as a dancer and performer. She has danced as a star in all the great ballets, but has devoted most of the past decade to contemporary ballet. Her work is breathtaking in its scope and originality.

Guillem has just turned fifty, and, with the same clarity of purpose that has marked all her career decisions, has decided to stop dancing. Yet she is not showing any decline in skill. Her performance yesterday was a masterpiece of virtuosity, her technique unparalleled, her famously athletic body still dazzling in the shapes it achieves, seemingly without effort.

As she writes herself in the program notes: "Why stop? Very simply, because I want to end while I am still happy doing what I do with pride and passion."

Performance relies on the body and the mind, and depends on the faculties of both. All performers live in anxiety of the failure of their tools: the body slows down, the muscles become less strong, the voice breaks. The mind fails. Dancers and opera singers are particularly aware of this, yet it affects all performers. A pianist known in her youth for extreme virtuosity may find as she ages that her playing must change. The fingers are less strong, the tendons tighter, and the spectacular brio of youth is gone. Yet the pianist is not necessarily done: a new maturity of playing, a new voice can emerge, as the performance changes to adapt to the new reality of the body. I remember hearing two recordings of the great violinist Heifetz playing the same concerto, once in his thirties, once on his final concert in his 80s. There was a noticeable difference in the playing. The youthful performance was brilliant and assured, yet the performance at 80, slower, perhaps a little more tremulous, had found a new depth of lyrical expression to the music. Perhaps, when virtuosity is insufficient, the performer must find new richness in the work.

Guillem's choices of pieces yesterday reflected this. They highlighted precision, athleticism, and shear physical expressiveness of her dancer' body. In the first piece, choreographed for her by Akram Khan, she crawled onto stage, and then reproduced her career before our eyes: her body growing expressing ever more technique. She explored the meaning of performance for her, and in doing so, entered a strange, uncanny space. Her human body became inhuman, the years of practice and the natural talent allowing to explore spaces that our bodies cannot enter. I watched as she lay on the floor in a posture that highlighted her over extended elbows and hyper flexible hips, and it was a strange thing. Virtuosity is other worldly. Yet the concern with the meaning of years of practice was a concern of maturity, of the artist wondering what it is they have done. Her other two pieces of the first half, where she danced with other dancers, seemed to me tinged with anxiety about the difficulties of collaboration. In one, Guillem appeared only for the briefest instant to disturb an exquisite, tense pas de deux between two male dancers, who kept coming into and out of phase with each other, ending sequences of steps in the same pose, but taking different paths to get there, and then sometimes seeming to attack each other. Was this a meditation on the frustrations of collaboration, and perhaps, the dangers of assuming one's centrality on the stage, and ignoring all that has gone on before you entered? In another piece, she performed a frantic duet with another female dancer while a dazzling light pattern redefined the shape of the stage constantly. Sometimes the dancers tracked the shifting lights, sometimes they didn't, yet always they moved as pair. Was this about succession and legacy?

In the final piece, entitled simply "bye", Guillem danced alone. This almost seemed a private dance (obviously it was not). And when she was done, she simply walked into a crowd, and vanished.

Guillem called the show "life in progress". That title acknowledges many things: that her life is not over because she has ceased dancing, and so by extension, that her life is not co extensive with her dancing (after all, she was once not a dancer, and existed as such). As scientists and academics, we too need to ask how long we wish to perform, and recognize that our life is not co-extensive with our work. And we too can think about how our performance changes as youthful virtuosity gives way to the techne gained through maturity.

Like performers, there is little reason to do academic science if we are not happy doing it with pride and passion. And like performers, deciding to end doing science does not mean deciding to end living.

Guillem has just turned fifty, and, with the same clarity of purpose that has marked all her career decisions, has decided to stop dancing. Yet she is not showing any decline in skill. Her performance yesterday was a masterpiece of virtuosity, her technique unparalleled, her famously athletic body still dazzling in the shapes it achieves, seemingly without effort.

As she writes herself in the program notes: "Why stop? Very simply, because I want to end while I am still happy doing what I do with pride and passion."

Performance relies on the body and the mind, and depends on the faculties of both. All performers live in anxiety of the failure of their tools: the body slows down, the muscles become less strong, the voice breaks. The mind fails. Dancers and opera singers are particularly aware of this, yet it affects all performers. A pianist known in her youth for extreme virtuosity may find as she ages that her playing must change. The fingers are less strong, the tendons tighter, and the spectacular brio of youth is gone. Yet the pianist is not necessarily done: a new maturity of playing, a new voice can emerge, as the performance changes to adapt to the new reality of the body. I remember hearing two recordings of the great violinist Heifetz playing the same concerto, once in his thirties, once on his final concert in his 80s. There was a noticeable difference in the playing. The youthful performance was brilliant and assured, yet the performance at 80, slower, perhaps a little more tremulous, had found a new depth of lyrical expression to the music. Perhaps, when virtuosity is insufficient, the performer must find new richness in the work.

Guillem's choices of pieces yesterday reflected this. They highlighted precision, athleticism, and shear physical expressiveness of her dancer' body. In the first piece, choreographed for her by Akram Khan, she crawled onto stage, and then reproduced her career before our eyes: her body growing expressing ever more technique. She explored the meaning of performance for her, and in doing so, entered a strange, uncanny space. Her human body became inhuman, the years of practice and the natural talent allowing to explore spaces that our bodies cannot enter. I watched as she lay on the floor in a posture that highlighted her over extended elbows and hyper flexible hips, and it was a strange thing. Virtuosity is other worldly. Yet the concern with the meaning of years of practice was a concern of maturity, of the artist wondering what it is they have done. Her other two pieces of the first half, where she danced with other dancers, seemed to me tinged with anxiety about the difficulties of collaboration. In one, Guillem appeared only for the briefest instant to disturb an exquisite, tense pas de deux between two male dancers, who kept coming into and out of phase with each other, ending sequences of steps in the same pose, but taking different paths to get there, and then sometimes seeming to attack each other. Was this a meditation on the frustrations of collaboration, and perhaps, the dangers of assuming one's centrality on the stage, and ignoring all that has gone on before you entered? In another piece, she performed a frantic duet with another female dancer while a dazzling light pattern redefined the shape of the stage constantly. Sometimes the dancers tracked the shifting lights, sometimes they didn't, yet always they moved as pair. Was this about succession and legacy?

In the final piece, entitled simply "bye", Guillem danced alone. This almost seemed a private dance (obviously it was not). And when she was done, she simply walked into a crowd, and vanished.

Guillem called the show "life in progress". That title acknowledges many things: that her life is not over because she has ceased dancing, and so by extension, that her life is not co extensive with her dancing (after all, she was once not a dancer, and existed as such). As scientists and academics, we too need to ask how long we wish to perform, and recognize that our life is not co-extensive with our work. And we too can think about how our performance changes as youthful virtuosity gives way to the techne gained through maturity.

Like performers, there is little reason to do academic science if we are not happy doing it with pride and passion. And like performers, deciding to end doing science does not mean deciding to end living.

Saturday, 17 October 2015

Notes of a prodigal paleontologist

I am at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meetings in Dallas, Texas. I haven't been to this meeting in two years, during which I've done very little paleontology, and in fact rather little evolutionary work. The last time I came, I was presenting the final part of my dissertation work. That presentation was on the results of four years of solid, focused work. This year, I presented the results of a side project collaboration which I am not leading (I'm the methods guy). The feeling was very different.

SVP was my main professional academic meeting throughout grad school. It was the first meeting I attended, the first meeting I presented at. I have good friends, colleagues and mentors here. In many ways, it still feels like home. My dissertation project was inspired largely by a single talk I saw at SVP Cleveland seven years ago. By the end of my time in graduate school, I almost felt I was beginning to get a certain reputation as a methods person. At the very least, the other paleontologists in that sub community knew of me.

But for the past two years, I've been doing something completely different, and attending different meetings, where I know far fewer people, and am known by almost none. I'm somewhat out of the loop on the paleo literature, having had to devote my reading efforts to understanding the literature of swallowing physiology and dysphagia. The abstract I put together for the meeting was on a completely different paleontological problem to what my dissertation was on (using the same methods). My co-author was the dinosaur footprints expert. I would be presenting to his peers. And I also wondered (giving my growing interest in comparative physiology and neural mechanism of muscular function) whether I would still be interested and excited by the meeting. And whether people here would still be interested and excited by me.

SVP is a surprisingly eclectic meeting, certainly I think more so than people not in the society might think. As paleontology has become more and more focused on understanding the biology of extinct animals over the past half century, the amount of comparative functional morphology at the meetings has increased. The advent of tree based methods for reconstructing evolutionary history has meant that many questions that were once the purview of fossil analysis can now be approached by looking only, or mostly, at living animals. Thirty years ago, these innovations resulted in virulent fights in the paleo community. Now, a quiet synthesis has occurred, and no one is surprised to see a talk discussing comparative gestation times in extant mammals follow the description of a new fossil. The first day, I struggled a little to find my feet. Much like when I return to France after a long break, the thoughts and ideas seemed to come from far away, and I wasn't entirely sure I could engage with anything. As the week wore on however, the language came back, as did the excitement. What's more, my new research was causing me to look for new things in the meeting. The paleoneurology (yes, it's a thing) and ontogeny talks were now on my radar. And I found (always a good sign), that many abstracts had ideas that paralleled some of my thinking, both on the questions from my dissertation, and on my new questions.

On the very first day, I saw a talk by one of the big guys in understanding early mammalian evolution. He was discussing the evolution of the unique mammalian nasal respiratory tract, and talking about the complex integration of smell, taste, chewing and respiration in mammals. Immediately I began tying in what he was saying with my thoughts on the neurophysiology of swallowing, and in particular how the mammalian oropharynx goes through a major neurological, behavioral and anatomical transition at infant weaning. After, I went to talk to him, and he seemed interested enough in my ideas, that were not coming from the study of fossils, but from my experimental work, that he wanted to know more. It was a reminder that I still belong here.

This morning, the last day of the conference, there was an entire symposium dedicated to the methodology I became an expert in as a paleontologist (an aspect of which had formed the basis of my own talk). I watched as several people, whose work I had always admired as a graduate student, got up and gave more talks. Talks I found compelling, novel and exciting. I now have new ideas I'd like to explore in my old data, and I'm reminded why I did this thing in the first place.

I came to this meeting unsure of what I would find, and more out of a desire not to abandon my identity as a paleontologist. I'm leaving reinvigorated, my ideas about the evolution of mammalian oropharyngeal function clarified, and new ideas of how I could link what I do to the fossil record emerging.

As I work on my transition to independence as a researcher, I'm glad to find that I'm still energised by the work and ideas of my earliest mentors, and that I in turn can energise them with what I'm doing as an experimental biologist. My path to this point makes more sense to me now, and I'm glad to know I still belong at this meeting, even as I make a place for myself at others.

SVP was my main professional academic meeting throughout grad school. It was the first meeting I attended, the first meeting I presented at. I have good friends, colleagues and mentors here. In many ways, it still feels like home. My dissertation project was inspired largely by a single talk I saw at SVP Cleveland seven years ago. By the end of my time in graduate school, I almost felt I was beginning to get a certain reputation as a methods person. At the very least, the other paleontologists in that sub community knew of me.

But for the past two years, I've been doing something completely different, and attending different meetings, where I know far fewer people, and am known by almost none. I'm somewhat out of the loop on the paleo literature, having had to devote my reading efforts to understanding the literature of swallowing physiology and dysphagia. The abstract I put together for the meeting was on a completely different paleontological problem to what my dissertation was on (using the same methods). My co-author was the dinosaur footprints expert. I would be presenting to his peers. And I also wondered (giving my growing interest in comparative physiology and neural mechanism of muscular function) whether I would still be interested and excited by the meeting. And whether people here would still be interested and excited by me.

SVP is a surprisingly eclectic meeting, certainly I think more so than people not in the society might think. As paleontology has become more and more focused on understanding the biology of extinct animals over the past half century, the amount of comparative functional morphology at the meetings has increased. The advent of tree based methods for reconstructing evolutionary history has meant that many questions that were once the purview of fossil analysis can now be approached by looking only, or mostly, at living animals. Thirty years ago, these innovations resulted in virulent fights in the paleo community. Now, a quiet synthesis has occurred, and no one is surprised to see a talk discussing comparative gestation times in extant mammals follow the description of a new fossil. The first day, I struggled a little to find my feet. Much like when I return to France after a long break, the thoughts and ideas seemed to come from far away, and I wasn't entirely sure I could engage with anything. As the week wore on however, the language came back, as did the excitement. What's more, my new research was causing me to look for new things in the meeting. The paleoneurology (yes, it's a thing) and ontogeny talks were now on my radar. And I found (always a good sign), that many abstracts had ideas that paralleled some of my thinking, both on the questions from my dissertation, and on my new questions.

On the very first day, I saw a talk by one of the big guys in understanding early mammalian evolution. He was discussing the evolution of the unique mammalian nasal respiratory tract, and talking about the complex integration of smell, taste, chewing and respiration in mammals. Immediately I began tying in what he was saying with my thoughts on the neurophysiology of swallowing, and in particular how the mammalian oropharynx goes through a major neurological, behavioral and anatomical transition at infant weaning. After, I went to talk to him, and he seemed interested enough in my ideas, that were not coming from the study of fossils, but from my experimental work, that he wanted to know more. It was a reminder that I still belong here.

This morning, the last day of the conference, there was an entire symposium dedicated to the methodology I became an expert in as a paleontologist (an aspect of which had formed the basis of my own talk). I watched as several people, whose work I had always admired as a graduate student, got up and gave more talks. Talks I found compelling, novel and exciting. I now have new ideas I'd like to explore in my old data, and I'm reminded why I did this thing in the first place.

I came to this meeting unsure of what I would find, and more out of a desire not to abandon my identity as a paleontologist. I'm leaving reinvigorated, my ideas about the evolution of mammalian oropharyngeal function clarified, and new ideas of how I could link what I do to the fossil record emerging.

As I work on my transition to independence as a researcher, I'm glad to find that I'm still energised by the work and ideas of my earliest mentors, and that I in turn can energise them with what I'm doing as an experimental biologist. My path to this point makes more sense to me now, and I'm glad to know I still belong at this meeting, even as I make a place for myself at others.

Labels:

Early career,

Grad school,

paleontology,

postdoc,

science

Thursday, 1 October 2015

Coming to America

Why did I move to America? Because I'd always wanted to. Even when applying to undergrad, I did a cursory search of Harvard's website (this will immediately tell you something of what I thought about America, but no matter). I ruled it out as too expensive (and I resented the idea of having to take an extra exam), but I probably gave it more serious consideration than I did French university, and I'm a French citizen.

It is difficult, I think, for Americans, particularly the academically inclined, liberal kind, to truly understand the hypnotic fascination that America (before 9/11 in particular) could have on Europeans. Your cinema and television exported a culture of sophisticated glamour. Even the world of your cheesy soap operas (Baywatch, Sunset Beach, Dawson's creek, The OC) were so much more exciting than the dour drama of our British offerings. America seemed alive, and huge, and beautiful.

To put it this way: there was only ever one trip I wanted really to take, and that was to the statue of Liberty. By the time I had moved to America, I had already been here five times. The first ever trip I took to America in 1993 was the fulfillment of an already years long dream, and I didn't even get to go to Disneyworld. The statue of Liberty was enough.

And so, when I decided to go to grad school, I decided I would try to do so in America. I had no excellent reason beyond "why not fulfill two dreams in one?" I would become a paleontologist, and I would move to America. Both things I had wanted to do since I was less than ten.

But fulfilling childish dreams as a adult has costs. I suspected, applying for grad school in my early 20s, that things might end up more complicated than a five year jaunt across the Atlantic. One does not with impunity embark on a major life change in one's early twenties.

It is now 8 years since I first came to the US, and I have been here 7 of those last 8 years. I am now married to an American man. I have paid taxes in the US for more years than I have in England (even though I am ineligible to vote). I know the history, geography and culture of this country as well as I know that of France and England, and as well as many Americans. Yet I am not an American. I am a French and English man, here by choice and circumstance.

Many academics get used to international moves. Yet I get the impression that few choose those moves. I chose mine: I applied for PhDs in the US. And I knew what I was risking. Yet I did not know perhaps how much. This week I was applying for jobs back home. My husband and I have only the vaguest idea of how we would mesh his career goals with me moving back the UK. As much as part of me yearns to be closer to my friends and family, in some ways, that seems almost more complicated than staying here and flying home once a year or so. Yet what shocked me more was that I had no idea HOW to apply for a job in Britain. All my tacit knowledge in reading job apps, all my professional skills, all my wordsmithing were tailored to the American job market. Faced with a British job application, I was stumped.

I should not be surprised by this. I am the second generation in my family to drift between countries and cultures. My mother moved from France to England in 1973, and has lived as a French expat in London since then, awkwardly balanced between a culture she no longer entirely understands, and a culture she has never entirely understood. My siblings, I, and many of our friends are a syncretic mish mash, knowing the work practices of the English and the social practices of the French and only truly feeling comfortable when surrounded by other binationals who get the feeling of never quite fitting in. And I've added America to that mix. It is my home, yet I am not at home here.

This weekend, I spoke with my mother, as I do every week. We talked about my career goals, and about my husband and I. As I told about jobs in the UK I was applying for, to convince her I cared and was not a bad son, she asked me what my husband would do if I moved back to the UK. I answered that for his career, we would probably be apart a couple more years. Without hesitating, my mother told me that she would travel to see me wherever I was in the world, and that I should think about my husband and I as a couple when making career choices. She lifted a great weight from my shoulders, at the cost of not calling her youngest son home.

I have been true to myself in the geographical choices I have made (well, apart from Ohio. Ohio was not part of the plan). I have no regrets. But the life of the voluntary expat comes with costs, all the more complicated to weigh and measure in that they are in part self inflicted. I was not forced to come to America. What does that say about my attachment to my family? And if I refuse to consider myself American, then how do I deal with having my professional and family life here? Expatriation bears a toll, and as more academics become more international, more of us bear those secret bruises.

It is difficult, I think, for Americans, particularly the academically inclined, liberal kind, to truly understand the hypnotic fascination that America (before 9/11 in particular) could have on Europeans. Your cinema and television exported a culture of sophisticated glamour. Even the world of your cheesy soap operas (Baywatch, Sunset Beach, Dawson's creek, The OC) were so much more exciting than the dour drama of our British offerings. America seemed alive, and huge, and beautiful.

To put it this way: there was only ever one trip I wanted really to take, and that was to the statue of Liberty. By the time I had moved to America, I had already been here five times. The first ever trip I took to America in 1993 was the fulfillment of an already years long dream, and I didn't even get to go to Disneyworld. The statue of Liberty was enough.

And so, when I decided to go to grad school, I decided I would try to do so in America. I had no excellent reason beyond "why not fulfill two dreams in one?" I would become a paleontologist, and I would move to America. Both things I had wanted to do since I was less than ten.

But fulfilling childish dreams as a adult has costs. I suspected, applying for grad school in my early 20s, that things might end up more complicated than a five year jaunt across the Atlantic. One does not with impunity embark on a major life change in one's early twenties.

It is now 8 years since I first came to the US, and I have been here 7 of those last 8 years. I am now married to an American man. I have paid taxes in the US for more years than I have in England (even though I am ineligible to vote). I know the history, geography and culture of this country as well as I know that of France and England, and as well as many Americans. Yet I am not an American. I am a French and English man, here by choice and circumstance.

Many academics get used to international moves. Yet I get the impression that few choose those moves. I chose mine: I applied for PhDs in the US. And I knew what I was risking. Yet I did not know perhaps how much. This week I was applying for jobs back home. My husband and I have only the vaguest idea of how we would mesh his career goals with me moving back the UK. As much as part of me yearns to be closer to my friends and family, in some ways, that seems almost more complicated than staying here and flying home once a year or so. Yet what shocked me more was that I had no idea HOW to apply for a job in Britain. All my tacit knowledge in reading job apps, all my professional skills, all my wordsmithing were tailored to the American job market. Faced with a British job application, I was stumped.

I should not be surprised by this. I am the second generation in my family to drift between countries and cultures. My mother moved from France to England in 1973, and has lived as a French expat in London since then, awkwardly balanced between a culture she no longer entirely understands, and a culture she has never entirely understood. My siblings, I, and many of our friends are a syncretic mish mash, knowing the work practices of the English and the social practices of the French and only truly feeling comfortable when surrounded by other binationals who get the feeling of never quite fitting in. And I've added America to that mix. It is my home, yet I am not at home here.

This weekend, I spoke with my mother, as I do every week. We talked about my career goals, and about my husband and I. As I told about jobs in the UK I was applying for, to convince her I cared and was not a bad son, she asked me what my husband would do if I moved back to the UK. I answered that for his career, we would probably be apart a couple more years. Without hesitating, my mother told me that she would travel to see me wherever I was in the world, and that I should think about my husband and I as a couple when making career choices. She lifted a great weight from my shoulders, at the cost of not calling her youngest son home.

I have been true to myself in the geographical choices I have made (well, apart from Ohio. Ohio was not part of the plan). I have no regrets. But the life of the voluntary expat comes with costs, all the more complicated to weigh and measure in that they are in part self inflicted. I was not forced to come to America. What does that say about my attachment to my family? And if I refuse to consider myself American, then how do I deal with having my professional and family life here? Expatriation bears a toll, and as more academics become more international, more of us bear those secret bruises.

Tuesday, 8 September 2015

Return on investment, limited ressources and impossible hedges: the postdoc job search

I submitted my first job application for a faculty position last week. It's the first of around 30 opening I currently have listed. The application package (the American Standard: CV, cover letter, research statement, statement of teaching philosophy), took about a week or two to craft. I looked back over old letters I had written three years ago (for which I had already studied the internet intensely), judged them poor, rewrote them. I solicited, and got very good, feedback from my PI and two other professors in the department who know me. One is an associate professor, mid career, established in his field. The other is a pre-tenure, but very successful, assistant professor. The job itself was a neurophysiology position at a research school with a significant budget. And so all the materials will have to be recrafted for the more teaching focused schools, or the anatomy departments, or the more evolutionary and paleontological positions.

While I am working on these job packets, I am hard at work keeping the analysis and writing momentum we have developed in the group. I submitted my second first author paper from my postdoc for review last week, and next week I will take three days to finally revise and resubmit my third dissertation paper (which has been sitting on my hard drive for a year at this point). We have just finished a run of animal experiments, and there are at least two more first author papers (and several middle authors where I will be called upon for analysis) sketched out that could be ready by january.

My PI came and talked to me a couple of days ago. The R01 I'm on is in its final year, and we have not yet had a renewal. She informed me that my position is funded for certain until January 2017. If she gets refunded, the pressure is off. If not, I think that a few favours can be called in to complete that year, but no guarantees. To all intents and purposes, it is in my best interests to get a job this year, after two years in the postdoc.

Academic job applications are laborious, more so than private sector ones. More information is requested, the process is more drawn out, a greater research investment is expected at every stage of the process. And yet all that work is ancillary. Or, more specifically, it is icing. Grant, publications, research: those are the hard substrate you need for the crafting of the job documents to be even worth the effort. All these things take time, huge amounts of time. As a graduate student, or a postdoc, especially in a one grant lab like mine, time can suddenly become an exceptionally rare commodity. Like at the end of graduate school, I am on a timer if I don't want to face a serious gap in income. I have to maximize the ROI on the time I have. And knowing where to maximize that ROI is... non trivial. Obviously, more papers is better. But at this point, most papers I submit now will not be in press by the time applications close on most of the jobs I have lined up. Is a big list of in reviews worth it? How much is it worth relative to getting half a dozen more jobs applications out? After all, publication from the lab will help my PI's grant efforts, which also are of concern to me at this point.

I was in a similar bind at the end of grad school: I had no publications, my dissertation was unfinished, and I had no job lined up, a year away from cessation of funding and the end of my F1 visa. How to maximise my time? In the end, I wasted a few months on job applications: I got the very firm message that an ABD grad student with no pubs was not a hirable commodity. So I finished the dissertation, and headed back to the UK to live with my mother. I spent a year unemployed, applying for jobs and getting my first two papers out. It was not ideal, and owing to life circumstances not a scenario I can afford to repeat.

Which brings me to my next point in this rambling post. I have to prepare for the eventuality that I won't get a faculty position. With the current data on postdoc placement rates, all graduate students and postdocs need to hedge against not making it in academia. Yet what constitutes a good hedge? From my experience outside academia (which was before the recession), I know that field moves without experience are difficult. Again, you need to invest either capital (ie a nest egg to tide you over, difficult on a postdoc salary) or time to build useful contacts and experience. Time, which as I have mentioned, is a limited commodity when on a fixed term appointment.

I maintain that the challenges faced by people like me are not unique in kind to academia. Fixed term gigs, low starting salaries, competition for permanent positions, the open ended nature of projects that can expand to fill all available time, the constant need to re-invent yourself, even the need to be highly mobile, can be found in so many other industries where young graduates now end up (law, medicine, consulting, finance, tech, game development). But the degree, and specific combinations of these factors, combined with an idiosyncratic job application process that is mostly useless for getting jobs outside of academia, do present unique challenges that can hamstring young people in academic science trying to keep their lives together. And the combination of lack of capital and lack of time means that efficiently hedging for the high likelihood of having to operate a career move is a unique challenge. On this, young academics are in need of mentoring.

While I am working on these job packets, I am hard at work keeping the analysis and writing momentum we have developed in the group. I submitted my second first author paper from my postdoc for review last week, and next week I will take three days to finally revise and resubmit my third dissertation paper (which has been sitting on my hard drive for a year at this point). We have just finished a run of animal experiments, and there are at least two more first author papers (and several middle authors where I will be called upon for analysis) sketched out that could be ready by january.

My PI came and talked to me a couple of days ago. The R01 I'm on is in its final year, and we have not yet had a renewal. She informed me that my position is funded for certain until January 2017. If she gets refunded, the pressure is off. If not, I think that a few favours can be called in to complete that year, but no guarantees. To all intents and purposes, it is in my best interests to get a job this year, after two years in the postdoc.

Academic job applications are laborious, more so than private sector ones. More information is requested, the process is more drawn out, a greater research investment is expected at every stage of the process. And yet all that work is ancillary. Or, more specifically, it is icing. Grant, publications, research: those are the hard substrate you need for the crafting of the job documents to be even worth the effort. All these things take time, huge amounts of time. As a graduate student, or a postdoc, especially in a one grant lab like mine, time can suddenly become an exceptionally rare commodity. Like at the end of graduate school, I am on a timer if I don't want to face a serious gap in income. I have to maximize the ROI on the time I have. And knowing where to maximize that ROI is... non trivial. Obviously, more papers is better. But at this point, most papers I submit now will not be in press by the time applications close on most of the jobs I have lined up. Is a big list of in reviews worth it? How much is it worth relative to getting half a dozen more jobs applications out? After all, publication from the lab will help my PI's grant efforts, which also are of concern to me at this point.

I was in a similar bind at the end of grad school: I had no publications, my dissertation was unfinished, and I had no job lined up, a year away from cessation of funding and the end of my F1 visa. How to maximise my time? In the end, I wasted a few months on job applications: I got the very firm message that an ABD grad student with no pubs was not a hirable commodity. So I finished the dissertation, and headed back to the UK to live with my mother. I spent a year unemployed, applying for jobs and getting my first two papers out. It was not ideal, and owing to life circumstances not a scenario I can afford to repeat.

Which brings me to my next point in this rambling post. I have to prepare for the eventuality that I won't get a faculty position. With the current data on postdoc placement rates, all graduate students and postdocs need to hedge against not making it in academia. Yet what constitutes a good hedge? From my experience outside academia (which was before the recession), I know that field moves without experience are difficult. Again, you need to invest either capital (ie a nest egg to tide you over, difficult on a postdoc salary) or time to build useful contacts and experience. Time, which as I have mentioned, is a limited commodity when on a fixed term appointment.

I maintain that the challenges faced by people like me are not unique in kind to academia. Fixed term gigs, low starting salaries, competition for permanent positions, the open ended nature of projects that can expand to fill all available time, the constant need to re-invent yourself, even the need to be highly mobile, can be found in so many other industries where young graduates now end up (law, medicine, consulting, finance, tech, game development). But the degree, and specific combinations of these factors, combined with an idiosyncratic job application process that is mostly useless for getting jobs outside of academia, do present unique challenges that can hamstring young people in academic science trying to keep their lives together. And the combination of lack of capital and lack of time means that efficiently hedging for the high likelihood of having to operate a career move is a unique challenge. On this, young academics are in need of mentoring.

Labels:

Early career,

Grad school,

Mentorship,

money,

postdoc,

work

Tuesday, 18 August 2015

Why I read the introduction and discussion of papers

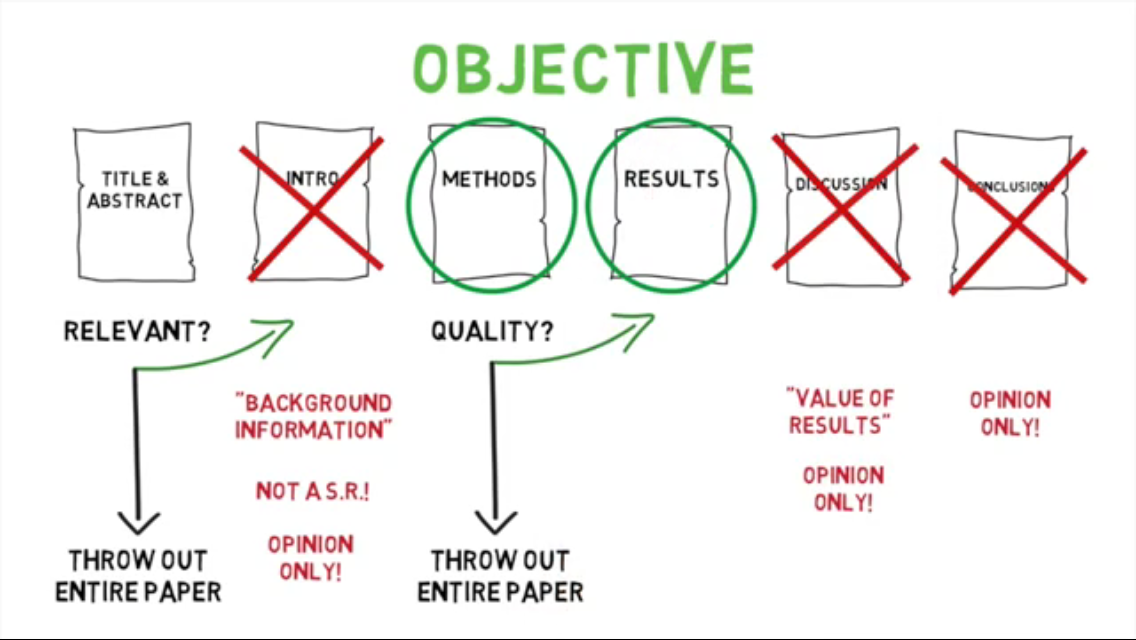

Over the past year, I've heard several times the sentiment that introductions and discussions of papers are not worth the .pdf memory they take up. Most recently, it took the form of the following cartoon passed around twitter.

|

| Cartoon by Anthony Crocco |

But I've had this discussion in person too, with assistant professors in our department. And I just don't get it. To me, a paper without the introduction and the discussion is almost literally nonsensical.

The intro, discussion, and conclusion have value because I don't view them as opinion, but as argument. The introduction should set up WHY the problem is interesting to the field, and why the approach chosen is relevant. This isn't just set up. It tells me a number of useful things: whether the person knows what they are doing with regard to the broader intellectual climate they are working in for one, but also, their thoughts on why the problem is important may not be my own. Their thinking, as detailed in the introduction, may modify, interrogate, change my own. And their thoughts about why the work is worth doing will guide 1) how they did it, and 2) what they intended to get out of it (which is important, because that set up will color how they present BOTH the methods and the results).

What is written in a paper is never just a simple narrative of the work done and the results obtained. That is a stylistic conceit. So knowing the set up is essential for critically assessing the "objective" parts (which are not so objective).

But it is the dismissal of the discussion that makes me saddest. The implication that the discussion can be discarded means that what the authors think of their results is irrelevant. There may be fields (particle physics perhaps) where the results are entirely unambiguous. I have yet to encounter a biological problem in which that is the case. Moreover, the non linear hierarchical interaction of biological systems (from molecules to cells to organs to organisms to behavior to ecology to evolution) mean that from an integrated biology perspective, I want to know about potential implications of the resultsfor connected elements of the biological hierarchy of organization. Again, a well crafted discussion is an argument, and a source of ways forward, not the spewing of opinion.

But perhaps what makes me saddest about the sentiment expressed in that cartoon is the solipsistic vision of science it produces. A focus on methods and results discounts the intellectual work, the scholarship done by your peers. It views others' work solely in light of how it might relate to one's own, and assumes that modes of thought about scientific problems are already so fixed, that nothing new will ever be found under the sun. This is not my experience of science.

In my field (evolutionary biology), one of the most important events that ever occurred was the Modern Synthesis. Over the course of ten to fifteen years, a disparate group of biologists came together to generate the modern understanding of evolution by natural selection, rooted in population genetics. The modern synthesis involved no ground breaking discoveries, and happened before we even properly understood the molecular mechanisms of heredity. The modern synthesis was the result of years of discussion and argument, culminating in, not a series of papers detailing new methods and new techniques, but in a series of books detailing a new way of thinking about biology. Crucially, it involved biologists from other fields understanding each other's work, despite being unfamiliar with each other's methods. If Mayr, Simpson, Dobzhansky, Huxley, and Stebbins had only engaged with their colleagues work through the schema of that cartoon, the modern synthesis would have been impossible.

In my field (evolutionary biology), one of the most important events that ever occurred was the Modern Synthesis. Over the course of ten to fifteen years, a disparate group of biologists came together to generate the modern understanding of evolution by natural selection, rooted in population genetics. The modern synthesis involved no ground breaking discoveries, and happened before we even properly understood the molecular mechanisms of heredity. The modern synthesis was the result of years of discussion and argument, culminating in, not a series of papers detailing new methods and new techniques, but in a series of books detailing a new way of thinking about biology. Crucially, it involved biologists from other fields understanding each other's work, despite being unfamiliar with each other's methods. If Mayr, Simpson, Dobzhansky, Huxley, and Stebbins had only engaged with their colleagues work through the schema of that cartoon, the modern synthesis would have been impossible.

Wednesday, 5 August 2015

Growth

I am currently writing a manuscript. It's the second first author manuscript to come from my postdoctoral work (a little under two years in), and hopefully it will be sent out for review in the next couple of weeks. Currently, my PI and I are sending it back and forth, querying the writing, clarifying the main points, realising (for me at least) some pretty large gaps in my knowledge of the litterature. But, at no point since I wrote the first draft have either my PI or I thought anything other than "this is a good manuscript, we just need to make it even better".

This is in many ways the paper I came here to write. It's the paper that shows that I understand how to do biological kinematics, that is how to study the movement of biological structures as organisms use them. As I've mentioned elsewhere, my background (which now seems quite far off) is in ecomorphology as applied to the fossil record. I correlated variation in mammalian bone morphology with known variation in broad categorical behavioral and ecological variables. But these broad classifications don't tell you about function, and so about the behavioral phenotype on which selection is acting. So I took this postdoc in part to learn how to ask those questions.

And here I am, writing a paper that does just that, yet also so much more than I had anticipated. The study we did was an experimental manipulation to see how a nerve lesion affected the movement of the tongue and oro-pharynx in our animal model. The work replicates a relatively frequent iatrogenic injury in premature human infants, and so it is clinically relevant. But the direction we have taken with this paper is so much more than that. We're using the changes we observe to make inference about the neurological control of these oro pharyngeal structures. My head has, for the past few weeks, been full of discussion of central pattern generators, afferent and efferent pathways.

With this paper, I feel like I have grown immensely as a scientist. I have become the integrative biologist I've always wanted to be. I'm not doing it in this paper yet, but I feel ready to connect my paleontological work and knowledge of mammalian evolution with my understanding of experimental organismal physiology.

I have an idea of the direction I want to head in as a paleontologist, as a evolutionary biologist, as a mammalian physiologist. And it's so much more than I thought it would be when I started this project hoping to learn about kinematics.

I'm heading out onto the job market this year. And my research statement will be nothing like the one I wrote three years ago when I was finishing my PhD. I think it will be so much more interesting. And I hope others will too.

This is in many ways the paper I came here to write. It's the paper that shows that I understand how to do biological kinematics, that is how to study the movement of biological structures as organisms use them. As I've mentioned elsewhere, my background (which now seems quite far off) is in ecomorphology as applied to the fossil record. I correlated variation in mammalian bone morphology with known variation in broad categorical behavioral and ecological variables. But these broad classifications don't tell you about function, and so about the behavioral phenotype on which selection is acting. So I took this postdoc in part to learn how to ask those questions.

And here I am, writing a paper that does just that, yet also so much more than I had anticipated. The study we did was an experimental manipulation to see how a nerve lesion affected the movement of the tongue and oro-pharynx in our animal model. The work replicates a relatively frequent iatrogenic injury in premature human infants, and so it is clinically relevant. But the direction we have taken with this paper is so much more than that. We're using the changes we observe to make inference about the neurological control of these oro pharyngeal structures. My head has, for the past few weeks, been full of discussion of central pattern generators, afferent and efferent pathways.

With this paper, I feel like I have grown immensely as a scientist. I have become the integrative biologist I've always wanted to be. I'm not doing it in this paper yet, but I feel ready to connect my paleontological work and knowledge of mammalian evolution with my understanding of experimental organismal physiology.

I have an idea of the direction I want to head in as a paleontologist, as a evolutionary biologist, as a mammalian physiologist. And it's so much more than I thought it would be when I started this project hoping to learn about kinematics.

I'm heading out onto the job market this year. And my research statement will be nothing like the one I wrote three years ago when I was finishing my PhD. I think it will be so much more interesting. And I hope others will too.

Labels:

biology,

Early career,

experiments,

postdoc,

science,

work

Monday, 27 July 2015

Familiar and Strange

I spent this weekend camping in the mountains of Virginia, near Goshen pass. It had been too long since I'd been in mountains. I saw the Milky Way one night (something which, having grown up in a city with some of the worst light pollution on the planet, still blows my mind). We swam in rivers, and hiked up to overlooks. The scenery was spectacular, and deeply rejuvenating. We stayed in the local recreational area, and camped by a river. The nearest town was twenty minutes drive away. The nearest grocery store nearly an hour. We chopped wood and built fire, bathed in the river (using biodegradable soap). And wherever we looked when in the mountains, we saw only wilderness as far as the eye could see. An endless thick forest rolling out over the valleys and mountains.

Although I grew up in a big city, I spent most of my holidays around mountains: the Vosges of Alsace, the Pennines of the Lake District, the Jura around Lake Geneva, the Alps of Tessino and Aosta. I've spent countless hours running through steep mountain side meadows, and hiking winding paths to spectacular overlooks, with views stretching out for hundreds of miles.

A few years ago, I was able to take my now husband to the small village in Alsace where I spent part of almost every summer holiday. My great grandmother lived there, and four generations of my mother's family has been there now. The Vosges mountains are old mountains, reaching their maximum height at about 1000m. Yet, because of the Ice Age, the valleys are glacial: flat bottomed and steep sided. This is hiking country, and has been in a semi organised fashion for over a hundred years. And so the paths that run from the village to the mountaintops are well known to me.

I took my husband on a mammoth 9 hour hike along these paths that four generations of my family have walked along. Paths that my aunt and cousins and siblings and mother know well. As we climbed up the steep walls of the valley, we passed from the forests to the high meadows, to this day still used as grazing pasture for the cattle that make the cheese for which the valley is famous. In those pastures, farms provide, as they have done for a century, rustic lunches for the hikers. Because this is France, these rustic lunches are delicious, fresh, and come with wine. Because this is Alsace, the wine is white, and the lunches are enormous. But they go a long way towards making 9 hour hikes bearable.

When you stand on the top of the Hohneck, the highest point of the hike, you look out over similar geology to what you see in the Appalachians: rolling hills, deep valleys. But the geography is totally different.

Here the land is patchwork. There are forests yes, but they are cut up by pastures, and the valley floor is cleared of trees, and dotted with villages. And all around the mountainsides, small farms, or old shepard's huts, or the odd old country house, are visible. Even after walking up nearly 500m, the land is still human.

Even in the most remote of Alpine valleys in Switzerland or Austria, one will see these marks of humans on the land. What is more, the landscape of Alsace is in some ways more ancient than that of Virginia: much of the Appalachians was once clear logged for wood and farmland. That is why Appalachian forests do not have millenial oaks like European ones do. But with the westward expansion, men moved on, and the forest grew back. In my overcrowded, ancient continent, people stayed.

The Appalachians, and the Vosges, are both rejuvenating to me. But when I stand on those mountaintops and gaze out at the landscape before me, on is familiar, and one is still a reminder that I am not at home. After seven years, even in those places I like most, I am still a stranger here. And, like all expats, I wonder that if I cease to be a stranger here, then that place where generations of my family have walked will cease to be home.

If I have children, will I show them the path up from their great great grandmother's house, through the valley their grandmother, uncles, aunts, father, and cousins played in, up to the mountaintop that looks over a landscape that their family has lived in for over a century? Or will I show them the endless rolling woods that their father discovered with their other father, that have almost no mark of man on them?

| |||

| The mountains of Virginia |

A few years ago, I was able to take my now husband to the small village in Alsace where I spent part of almost every summer holiday. My great grandmother lived there, and four generations of my mother's family has been there now. The Vosges mountains are old mountains, reaching their maximum height at about 1000m. Yet, because of the Ice Age, the valleys are glacial: flat bottomed and steep sided. This is hiking country, and has been in a semi organised fashion for over a hundred years. And so the paths that run from the village to the mountaintops are well known to me.

I took my husband on a mammoth 9 hour hike along these paths that four generations of my family have walked along. Paths that my aunt and cousins and siblings and mother know well. As we climbed up the steep walls of the valley, we passed from the forests to the high meadows, to this day still used as grazing pasture for the cattle that make the cheese for which the valley is famous. In those pastures, farms provide, as they have done for a century, rustic lunches for the hikers. Because this is France, these rustic lunches are delicious, fresh, and come with wine. Because this is Alsace, the wine is white, and the lunches are enormous. But they go a long way towards making 9 hour hikes bearable.

When you stand on the top of the Hohneck, the highest point of the hike, you look out over similar geology to what you see in the Appalachians: rolling hills, deep valleys. But the geography is totally different.

|

| The view from the Hohneck |

Even in the most remote of Alpine valleys in Switzerland or Austria, one will see these marks of humans on the land. What is more, the landscape of Alsace is in some ways more ancient than that of Virginia: much of the Appalachians was once clear logged for wood and farmland. That is why Appalachian forests do not have millenial oaks like European ones do. But with the westward expansion, men moved on, and the forest grew back. In my overcrowded, ancient continent, people stayed.

The Appalachians, and the Vosges, are both rejuvenating to me. But when I stand on those mountaintops and gaze out at the landscape before me, on is familiar, and one is still a reminder that I am not at home. After seven years, even in those places I like most, I am still a stranger here. And, like all expats, I wonder that if I cease to be a stranger here, then that place where generations of my family have walked will cease to be home.

If I have children, will I show them the path up from their great great grandmother's house, through the valley their grandmother, uncles, aunts, father, and cousins played in, up to the mountaintop that looks over a landscape that their family has lived in for over a century? Or will I show them the endless rolling woods that their father discovered with their other father, that have almost no mark of man on them?

Wednesday, 15 July 2015

An apology, and understanding

I was an ass on twitter last night. PIs and postdocs were shouting about the overtime threshold change, and I jumped in, riled up and angry and not paying enough attention to what was being said, so sure I was of what I was saying. I apologize.

I was made to realize (by someone with great patience) that much of the PI ambivalence to this announcement boils down to it adding yet another financial burden on labs whose margin of operation is already so thin as to be invisible. And so, once again, all our great science problems come back to the question of funding.

PI are, everywhere, trying to square an impossible circle, that keeps getting more complicated. And as much as we may think we understand, we postdocs are not squaring that circle. That burden is the PIs.

I still think this rule change is a rare victory for American workers' rights, after decades of seeing them eroded. I still think that the segue through the discussion of a postdoc's worth this weekend was unecessary, beside the point, and vicious. I still think that in the aggregate, this reform will be for the best. The key word there is aggregate.

But I am also reminded that any new law put forward without adequate funding may quickly become little more than window dressing. And that when it comes to its impact on workers paid by the public dollar, that may be what this law becomes.

In the immediate term, if the reform goes through as intended, I suspect HR memos will be sent, and PIs will watch their postdocs comings and goings a little closer. Maybe fewer marathon experiments will be scheduled back to back. Maybe fewer hours will be worked. Maybe this will actually be good for the long hours culture in academia (though I hear the overtime exempt PIs laugh darkly at this).

But what this ugky episode reminds us most, is that no matter how you cut, no matter what you reform, there isn't enough money for all the people in science right now. And until that's addressed, all reforms like these will have similar responses I fear.

I was made to realize (by someone with great patience) that much of the PI ambivalence to this announcement boils down to it adding yet another financial burden on labs whose margin of operation is already so thin as to be invisible. And so, once again, all our great science problems come back to the question of funding.

PI are, everywhere, trying to square an impossible circle, that keeps getting more complicated. And as much as we may think we understand, we postdocs are not squaring that circle. That burden is the PIs.

I still think this rule change is a rare victory for American workers' rights, after decades of seeing them eroded. I still think that the segue through the discussion of a postdoc's worth this weekend was unecessary, beside the point, and vicious. I still think that in the aggregate, this reform will be for the best. The key word there is aggregate.

But I am also reminded that any new law put forward without adequate funding may quickly become little more than window dressing. And that when it comes to its impact on workers paid by the public dollar, that may be what this law becomes.

In the immediate term, if the reform goes through as intended, I suspect HR memos will be sent, and PIs will watch their postdocs comings and goings a little closer. Maybe fewer marathon experiments will be scheduled back to back. Maybe fewer hours will be worked. Maybe this will actually be good for the long hours culture in academia (though I hear the overtime exempt PIs laugh darkly at this).

But what this ugky episode reminds us most, is that no matter how you cut, no matter what you reform, there isn't enough money for all the people in science right now. And until that's addressed, all reforms like these will have similar responses I fear.

Wednesday, 8 July 2015

This isn't about you

I've been trying of late not to blog based on twitter interactions so much, because I think I talk enough on twitter that I don't need to repeat myself on here. But the past few days discussion about the overtime directive has me feeling the need to expand on my thoughts slightly.

To recap, the Obama administration is directing the department of labor to raise the threshold for overtime exemption from $23,660 dollars a year to $50,000 dollars a year, on the basis that that threshold no longer reflects the intent of the law as was written.

Justin Kiggins over at the Spectroscope blogged about whether this would apply to postdocs, who are currently paid $42,000 and $56,000 on the NRSA pay scale set by NIH (I believe that the level are slightly less for NSF postdocs, but I have been unable to find clear figures). Thus, postdocs with less than 4 years postdoctoral experience may be concerned by this change (after 4 years NRSA pay scale reaches the new threshold). This was a reasonable point to make. And then all hell broke loose on twitter.

Initially, most postdocs were incredulous that such a thing as "overtime" could even apply to them. Even today, scientists on twitter are arguing that scientists are overtime exempt, pointing to the very directive that is subject to change. Others argued that fellows are already exempt from many of these labor laws. Which is true, but many postdocs are not fellows in a employment sense: if you are paid our of a PI grant such as a R01 and receive a W-2 with witholdings, you are, to all intents and purposes, an employee of the institutions at which you work (this is also why you are illegible for employee benefits, 403bs and such). Most postdocs were convinced that universities and NIH would do everything they could to find ways around this. Which is probably true, that is how labor reform goes. More disturbing to me was how many were convinced that it shouldn't apply to them. Arguments raged that our work could not be quantified (yes it can), that what we did didn't count as work anyway (yes it does), that we didin't fill time cards (indeed, because the current law does not require it). Anything but the status quo seemed unimaginable, and the very idea that may be a limitation of working hours inconceivable.

And then the PIs got involved, and it turned into a standard discussion of what postdocs are owed, what they worth, how we are entitled. We were called "giddy", despite having greeted this entire discussion with (in my view) excessive skepticism. We were warned darkly about what this might do to our employment prospects (by the very people who ordinarily would say that lowering the number of postdocs would be a good thing).

And here is where I lost it.

Because this reform is not about postdocs. As Kiggins pointed out, postdocs represent less than 1% of the people who may be affected. This reform is about bar, restaurant and store managers on $24,000 how work 60 hr weeks. This reform is about how nearly 9/10th of US earners are exempted under current legislation (back of an envelope calculations from here). This is about how, as the reaction of US postdoc shows, no one in this country actually believes in labor law anymore. No one believes that they can be protected from overwork, that pay should be proportional to hours worked as well as talent. No one even believes in the benefits their employer gives them. I have yet to meet a single person at my workplace who takes our (generous) 20 day vacation allowance. And trust me, it's not just because they love their work. I've spent enough time with Americans to know how they are socialized to view vacation as a professional liability.

And yes, laws like this have complex and difficult ramifications for small and medium enterprises. If PIs think finding an extra 6 grand for a postdoc will be hard, think of the restaurant manager trying to calculate whether or not to hire a second manager at 24K, pay the existing manager overtime, or bump her salary to the new threshold.

But when we argue about whether we should be exempt, we are not just doing ourselves a disfavour. We're making an argument that will be used by every boss in every sector against people paid far less and with worse career prospects.

So, PIs, postdocs: this rule is not about you. It is about fair labor compensation for all workers in the US, of which you happen to be a part. A little less onanistic navel gazing would suit you well at this point.

In 2000, France passed a law mandating a 35h working week for all salaried workers, with further limits on annual amounts of overtime worked. It was cumbersome and stupid, difficult to implement and the subject of much ridicule. But I would much rather come from that tradition then one that is so willing to believe its only right is to work more for less.

(As an aside, the current salary cap is low enough that most lab techs are also overtime exempt. Have you asked your tech how many hours she works lately?)

To recap, the Obama administration is directing the department of labor to raise the threshold for overtime exemption from $23,660 dollars a year to $50,000 dollars a year, on the basis that that threshold no longer reflects the intent of the law as was written.

Justin Kiggins over at the Spectroscope blogged about whether this would apply to postdocs, who are currently paid $42,000 and $56,000 on the NRSA pay scale set by NIH (I believe that the level are slightly less for NSF postdocs, but I have been unable to find clear figures). Thus, postdocs with less than 4 years postdoctoral experience may be concerned by this change (after 4 years NRSA pay scale reaches the new threshold). This was a reasonable point to make. And then all hell broke loose on twitter.

Initially, most postdocs were incredulous that such a thing as "overtime" could even apply to them. Even today, scientists on twitter are arguing that scientists are overtime exempt, pointing to the very directive that is subject to change. Others argued that fellows are already exempt from many of these labor laws. Which is true, but many postdocs are not fellows in a employment sense: if you are paid our of a PI grant such as a R01 and receive a W-2 with witholdings, you are, to all intents and purposes, an employee of the institutions at which you work (this is also why you are illegible for employee benefits, 403bs and such). Most postdocs were convinced that universities and NIH would do everything they could to find ways around this. Which is probably true, that is how labor reform goes. More disturbing to me was how many were convinced that it shouldn't apply to them. Arguments raged that our work could not be quantified (yes it can), that what we did didn't count as work anyway (yes it does), that we didin't fill time cards (indeed, because the current law does not require it). Anything but the status quo seemed unimaginable, and the very idea that may be a limitation of working hours inconceivable.

|

| The response to the possibility that labor laws might apply here |

And here is where I lost it.

Because this reform is not about postdocs. As Kiggins pointed out, postdocs represent less than 1% of the people who may be affected. This reform is about bar, restaurant and store managers on $24,000 how work 60 hr weeks. This reform is about how nearly 9/10th of US earners are exempted under current legislation (back of an envelope calculations from here). This is about how, as the reaction of US postdoc shows, no one in this country actually believes in labor law anymore. No one believes that they can be protected from overwork, that pay should be proportional to hours worked as well as talent. No one even believes in the benefits their employer gives them. I have yet to meet a single person at my workplace who takes our (generous) 20 day vacation allowance. And trust me, it's not just because they love their work. I've spent enough time with Americans to know how they are socialized to view vacation as a professional liability.

And yes, laws like this have complex and difficult ramifications for small and medium enterprises. If PIs think finding an extra 6 grand for a postdoc will be hard, think of the restaurant manager trying to calculate whether or not to hire a second manager at 24K, pay the existing manager overtime, or bump her salary to the new threshold.

But when we argue about whether we should be exempt, we are not just doing ourselves a disfavour. We're making an argument that will be used by every boss in every sector against people paid far less and with worse career prospects.

So, PIs, postdocs: this rule is not about you. It is about fair labor compensation for all workers in the US, of which you happen to be a part. A little less onanistic navel gazing would suit you well at this point.

In 2000, France passed a law mandating a 35h working week for all salaried workers, with further limits on annual amounts of overtime worked. It was cumbersome and stupid, difficult to implement and the subject of much ridicule. But I would much rather come from that tradition then one that is so willing to believe its only right is to work more for less.

(As an aside, the current salary cap is low enough that most lab techs are also overtime exempt. Have you asked your tech how many hours she works lately?)

Wednesday, 17 June 2015

The value of capable

Today was a tough day in the lab. Supertech and I are flying solo (PI is away), and we are running two weeks of experiments using a rather expensive, and rather delicate, piece of custom built equipment. The experiments are supposed to be straightforward. As today showed, "supposed" is the operative word here.

It should be noted that supertech and I (well, mostly supertech. I just help) are pretty anal about planning experiments. We put a lot of thought into how the experiments are going to run, and we test as much as we can beforehand. The reason for this is that once experiments start, there is no time to think. Baby animals are screaming to be fed, multiple multi hour surgeries need to be done, and we need to make sure that people don't get irradiated by the high powered fluoroscopes (there are two). The simple act of getting through experiments drains brains and nerves.

But even with the best laid plans, things go wrong. Not everything can be anticipated. Which lead to today, when our expensive piece of machinery (basically, a series of precise electronically controlled pumps) stopped working. With four screaming hungry pigs in the room.

As in turned out, a crucial piece of information had been left out when discussing the design of the system (before I or Supertech joined the lab). Why? Who knows. The same reason that, with hindsight, really obvious things are missed from experimental planning. Essentially, the pumps got fouled up by the radio opaque particulates in the liquid we pump. Two weeks of experiments and four animals were at stake.

Supertech and I then went into super capable mode. We troubleshooted the system every way we knew. I called the manufacturer, and confirmed what the issue was. We found a way to clean the pumps, and then started to work on solving the problem that our fluid had particles that were too large. Within an hour we had three possible solutions. Within two hours we had started to put in place all three. By seven pm this evening, Supertech and her husband had built a high volume filtering system that would remove the large particles from our suspension (we'd already by this point checked that this kept the solution radio opaque). Tomorrow experiments will resume, and we will only be one day behind.

As a lab team, supertech and I are capable. We can deal on the fly with most crises. When something goes wrong, within half an hour we have a plan, within a hour we're putting it in place. We brainstorm, prioritize, call people and get things fixed. She's better than I am, but I pull my weight. I don't think we've lost much more than a week on any experimental schedule, and that was due to unforeseen animal death. We have stayed overnight in the lab to care for sickly animals. We've harassed suppliers to get things overnighted. We've become conversant in technical topics we knew nothing about. We get things done.

For the science, this is great. For the animals, this is essential. But for us... I worry. I worry that capability, the ability to creatively solve problems on the fly, and to put in the effort to do it, doesn't always reap the rewards equivalent to its cost in hours and stress. I don't mean to impugn our PI. She treats us exceptionally well, recognizes our efforts, and has rewarded us with substantial autonomy and authority on the running of the lab. I mean rather, that the labor market since Taylor and Ford has been structured so as not to rely on the capable worker. To a manufacturer, the added value of a capable line worker is marginal compared to a merely adequate one. And in science, techs and postdocs (and graduate students) are somewhat like manufacturing labor. Yes, a good postdoc adds value to the lab, but how much value relative to a merely adequate one?

Many of my smart, capable friends in other jobs hide their capability, revealing it only to those they trust not to exploit it. Capable people need to learn to say no, because they get asked to do more than most, and all of the difficult, non rote tasks. And problem solving is tiring work.

I like being capable. I like not being helpless in the face of problems. But I worry that capability is a liability, because it becomes assumed, and because its value to the beneficiaries is less than its cost to those who do the capable work.