|

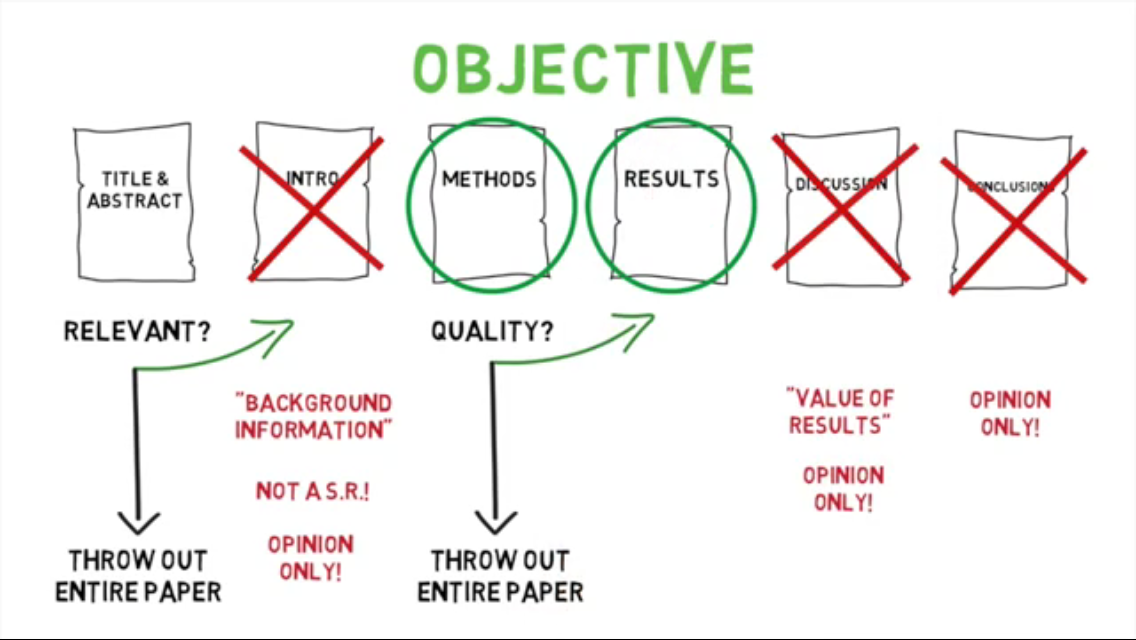

| Cartoon by Anthony Crocco |

But I've had this discussion in person too, with assistant professors in our department. And I just don't get it. To me, a paper without the introduction and the discussion is almost literally nonsensical.

The intro, discussion, and conclusion have value because I don't view them as opinion, but as argument. The introduction should set up WHY the problem is interesting to the field, and why the approach chosen is relevant. This isn't just set up. It tells me a number of useful things: whether the person knows what they are doing with regard to the broader intellectual climate they are working in for one, but also, their thoughts on why the problem is important may not be my own. Their thinking, as detailed in the introduction, may modify, interrogate, change my own. And their thoughts about why the work is worth doing will guide 1) how they did it, and 2) what they intended to get out of it (which is important, because that set up will color how they present BOTH the methods and the results).

What is written in a paper is never just a simple narrative of the work done and the results obtained. That is a stylistic conceit. So knowing the set up is essential for critically assessing the "objective" parts (which are not so objective).

But it is the dismissal of the discussion that makes me saddest. The implication that the discussion can be discarded means that what the authors think of their results is irrelevant. There may be fields (particle physics perhaps) where the results are entirely unambiguous. I have yet to encounter a biological problem in which that is the case. Moreover, the non linear hierarchical interaction of biological systems (from molecules to cells to organs to organisms to behavior to ecology to evolution) mean that from an integrated biology perspective, I want to know about potential implications of the resultsfor connected elements of the biological hierarchy of organization. Again, a well crafted discussion is an argument, and a source of ways forward, not the spewing of opinion.

But perhaps what makes me saddest about the sentiment expressed in that cartoon is the solipsistic vision of science it produces. A focus on methods and results discounts the intellectual work, the scholarship done by your peers. It views others' work solely in light of how it might relate to one's own, and assumes that modes of thought about scientific problems are already so fixed, that nothing new will ever be found under the sun. This is not my experience of science.

In my field (evolutionary biology), one of the most important events that ever occurred was the Modern Synthesis. Over the course of ten to fifteen years, a disparate group of biologists came together to generate the modern understanding of evolution by natural selection, rooted in population genetics. The modern synthesis involved no ground breaking discoveries, and happened before we even properly understood the molecular mechanisms of heredity. The modern synthesis was the result of years of discussion and argument, culminating in, not a series of papers detailing new methods and new techniques, but in a series of books detailing a new way of thinking about biology. Crucially, it involved biologists from other fields understanding each other's work, despite being unfamiliar with each other's methods. If Mayr, Simpson, Dobzhansky, Huxley, and Stebbins had only engaged with their colleagues work through the schema of that cartoon, the modern synthesis would have been impossible.

In my field (evolutionary biology), one of the most important events that ever occurred was the Modern Synthesis. Over the course of ten to fifteen years, a disparate group of biologists came together to generate the modern understanding of evolution by natural selection, rooted in population genetics. The modern synthesis involved no ground breaking discoveries, and happened before we even properly understood the molecular mechanisms of heredity. The modern synthesis was the result of years of discussion and argument, culminating in, not a series of papers detailing new methods and new techniques, but in a series of books detailing a new way of thinking about biology. Crucially, it involved biologists from other fields understanding each other's work, despite being unfamiliar with each other's methods. If Mayr, Simpson, Dobzhansky, Huxley, and Stebbins had only engaged with their colleagues work through the schema of that cartoon, the modern synthesis would have been impossible.